November 15, 2005

Two years ago, after witnessing first-hand the atrocities carried

out by the US military in the invasion and occupation of Iraq,

Private First Class Joshua Key decided to desert the US Army rather

than face redeployment in the criminal war.

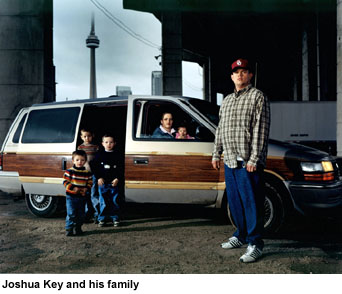

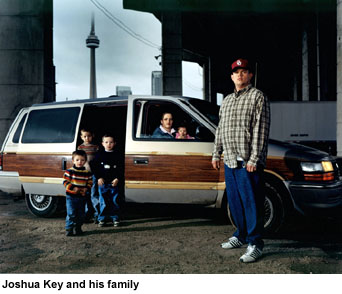

Key is now in Canada with his wife and four young children,

having joined a growing number of US soldiers who have fled there

seeking refugee status.

He spoke to the WSWS in Toronto shortly before moving with

his family to Gabriola Island, British Columbia, where they are

currently living.

When he returned to Fort Carson, Colorado on a two-week leave

at the end of November 2003, Joshua Key had already made the decision

that he was not going to return to the war in Iraq. After seven

months in the country, he did not want to participate in what

he described as crimes against the Iraqi people, who regarded

the American military as an unwanted and illegal occupation force.

He fled the base with his wife and three young children in

what would be 14 months of hiding out from the Army and law enforcement

before fleeing to Canada.

Born in 1978 in Guthrie, Oklahoma, Joshua Key grew up on a

ranch and dreamed of becoming a welder, but didn't have the

money to go through school to gain his certification. He met his

future wife Brandi at the age of 18, and together they had two

children with one more on the way when he met an Army recruiter

in February 2002. The recruiters promised him that he would be

assigned as bridge-builder in a non-deployable unit and assured

him that he would never see combat.

Key would later realize that the recruiters knew exactly what

to say to him, appealing to his lack of job security and health

care for himself and his family. Taking their assurances - that

they would never send the father of three small children into

combat and that he could acquire the skills needed for his trade - at

face value, he felt joining the Army was a sound decision.

Key went off to boot camp at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri by

the end of May 2002, and after nine weeks he was stationed at

Fort Carson, Colorado with the 43rd Company of Combat Engineers

in a rapid deployment unit. By the time he arrived, troops were

already being prepared to ship out to Kuwait in preparation for

the invasion of Iraq.

"I immediately had the feeling that I was going to go

despite all of their promises. As soon as they started to deploy

large numbers of troops to Kuwait, I was one of the first to leave

my base. I ended up in Iraq one month after the invasion in April

of 2003," Key recalled.

"I was with the 43rd Combat Engineer Company 2/3 ARC [Armed

Cavalry Regiment]. We were an asset to the Army because they could

put us anywhere they wanted. Our main objective, at least what

we thought it was when we first arrived, was to clear mines and

explosives. But after we got there, that wasn't the case

at all. We were never trained in how to raid houses and do traffic

control points, or how to institute curfews throughout cities

and make it work, but that's what we were doing. When we

arrived we expected the war to be over because that's the

way they made it sound. They told us that we were going to Ramadi,

a city of 300,000 Iraqis. I think there was only one platoon of

the 82nd Airborne there, and we were going in to keep control

of the city."

Key explained that they were all told that the Iraqi people

would welcome the American troops with open arms, one of the central

themes of the Bush administration's prewar propaganda. Like

the WMDs, it quickly proved a lie.

"When we first arrived it was difficult to tell much from

the expressions on the Iraqi people's faces - many people

were coming out of their houses just sort of standing there as

we would drive by," Key recalled.

"But then we learned that when Saddam was in power, if

his military rolled through the city, if everyone didn't

come out and run and cheer, his people would go into their houses

and give them a reality check. It was mandatory for people to

come out and cheer and clap. So it got to the point where we knew

that's just what the people are used to doing out of obligation.

So if they came out as we rolled through town, it was more because

they didn't want anything to happen to them or their homes.

It's what you would call habit-minus the clapping and

cheering. You actually saw anger in their faces."

The anger of the Iraqi people was fueled by widespread and

seemingly indiscriminate raids of their homes, routinely executed

with force and violence. The so-called intelligence that led to

targeting certain homes, Key said, was almost invariably groundless.

"You know, it [the intelligence] never panned out,"

Key said. "It could be something as simple as a wedding - where

it's a tradition for Iraqi people to fire guns in the air

when someone gets married - they've been doing that for

God knows how many years. So suddenly you have a QRF [Quick Reaction

Force] that moves in and starts raiding the home; and your commander

gets mad because there's nothing there and cordons off an

entire neighborhood and starts raiding every house."

"But usually you raid a house in the middle of the night

or early in the morning, almost always in the dark," Key

continued. "Most of the time we would pull up in civilian

vehicles. You drive up to an address. If the door was made out

of wood we would simply kick it in. Most of the time we would

put C-4 explosives in and just blow the door right off. You run

in there and people are running around and crying - let's

face it, it's pretty traumatic to have the door blown off

your home with C-4 in the middle of the night - and there's

usually about six or seven of us doing the raiding."

"You just clear room after room forcing everyone down

to the ground at gunpoint." Key added. "Then you zip-cuff

the males and throw them out the door. They say that we only do

that to the males that are over a certain age, but it generally

happens to every male in the house no matter how old. Thirteen

and fourteen year-old-boys are taken and zip-cuffed and thrown

out to a squad waiting out front. They get thrown into the back

of a five-ton truck and who knows what happens to them from there.

"People are detained for a very long time before they

ever see their families again, and I can say that I never saw

anyone returned and I definitely never returned anyone back to

their home myself. There are tens of thousands sitting in jails

for no reason whatsoever. Farming families that depend on the

men of the house to survive are ripped apart, with the women left

alone to fend for themselves."

The violence directed against US troops in the Iraq began to

escalate dramatically after the first several months of the invasion

as a direct result of the actions of the American forces against

the people of the country.

Key explained: "There was not a lot of violence at first.

I got to Iraq on the 27th of April, 2003. We were in Ramadi, and

for the first month there was hardly anything. Every now and then

you'd have small arms fire, but you weren't getting

mortar attacks and RPGs right and left, I mean it was real calm.

And then you start bringing in inexperienced soldiers into the

mix - they just move people around all the time so it's

never clear what we're doing. Everyone has the same objective,

to raid homes, patrol and do traffic control points, and Iraqi

civilians were getting shot up during all of it."

He continued, "Then you start getting people that are

real jumpy. When we got into the country we were told that if

you feel threatened, you shoot, and a lot of us did just that.

We all heard stories from some of the other platoons about soldiers

just shooting down people during raids or in the streets in neighborhoods,

because someone may have thrown a rock. Well the commanders say

if you can't tell the difference between a rock and a grenade,

go ahead and shoot. Me personally, I can tell the difference and

I was just not okay with that. I mean, come on, if you can't

handle a rock being thrown at you in a situation like this, then

there is something just not right. It has only made the Iraqi

people hate us that much more."

Checkpoints, or traffic control points, where there have been

numerous innocent civilians killed, became another focus of the

military's violence against the Iraqi population. Key recalled

a checkpoint that he was part of where American soldiers just

stood waving their hands in the air trying to get people to stop.

He explained how he had to pull a young wounded boy from a car

that was shot up by his squad for failing to stop when signaled.

"They just opened fire on the car because that's

what we're told to do," Key explained. "Rather

than think for a second, 'Hey, they don't know what

the hell we are saying here and it looks like a man and a child - let's

just hold off until they get up here,' they just open fire

on them. And then you have to pull the bodies out of the car and

take the injured off to the hospital, and you know they are just

innocent people."

Joshua Key discussed the war in Iraq with his wife Brandi in

depth on the eve of his deployment. There was the bitterness over

the recruiters' deception, but they tried their best to rationalize

what was happening. Digesting the news reports on the war, they

concluded that there were in fact terrorists and weapons of mass

destruction in Iraq. Brandi supported his going to war, telling

Joshua to get back in one piece as soon as possible. Joshua went,

but his opinion of the war changed almost as soon as he got to

Iraq.

"When do we get to go home?"

"Even in the first month I felt that we shouldn't

be there, and my only concern - and the concern of most of

the guys I knew - was when do we get to go home," Key

explained. "And then it got to the point where we were being

attacked every day - and we were being mortar attacked throughout

the night. We were in hell, and we couldn't even sleep.

"And then people you know start getting hurt, and there

were even some who were shooting themselves in the foot just to

come home. So then you're asking yourself, 'What's

going on here?' Obviously they don't have weapons of

mass destruction or they would have used them on us - we all

felt that way."

Key continued, "They have all these people searching for

this stuff - they can't find it. And all we're hearing

about is how highly guarded the oil fields are, and that this

is really the main concern for America. And then you start getting

demonstrations by the Iraqi people and they send you in there

to calm them down, and when you get there, they're all pissed

off with the US government.

"But they're pissed off at you because you are

the American government to them, when you are actually just a

soldier doing what you're told. And they're asking you,

'Why the hell are you guys still here? Why are you monopolizing

our Benzine [gas]? Why are you here?' I mean, I'd like

to tell them the truth: 'We're here to take your oil,

take all of your natural resources;' and 'How long are

you going to be here for? Well, we're gonna be here forever.'

You're not supposed to say that of course, but that's

what I wanted to say all the time."

Key summed up the rapid transformation of his views on the

war - and those of other soldiers.

"At first it didn't matter if I was going to die

or not because we were dying for a purpose - you're dying

because your country is at war and we had to take care of Saddam

Hussein," he said. "He was a dictator and you're

thinking of it all as sort of a Hitler situation. But then it

sinks in - the lies, and you start getting mad - your friends

are getting hurt and then you start thinking, 'Man, if I

die for this, what did I die for?'

"And everybody's asking the same thing, 'If

I die here, what the hell did I die for?' Well, we died for

the greed of President Bush. We died so his friends' companies

can thrive over in the Middle East. And it got to the point that

I realized I wasn't going to die for that, and I wasn't

going to sit in prison for it either."

"Most of the Joes felt that way," Key continued,

"at least those with a conscience - most of the guys like

myself with ranks up to E-5, and after that it becomes all political.

For the officers it's a life deal, but even some of them

felt that way.

"At one point I had a squad leader who was a Staff Sergeant

who was getting ready to be promoted to Sergeant First Class.

He'd been in the military for 16 years, and he told me 'When

I get home, I'm not going to do this shit again, I'm

getting out as fast as possible because I don't know what

we're doing here.' I think that demoralized us all."

Questioning the purpose of the US invasion and occupation of

Iraq, Key attests, was more prevalent within the ranks than anyone

on the outside knew. Many were constantly asking - in some

cases to their superiors - why they were there. This question

was all too frequently driven home with incidents of devastating

violence.

Key explained, "One of my [squad] sergeants got his leg

blown off. I used to talk to him even before that happened, and

even he couldn't give us a reason for us being there. All

of us would ask him, 'What is the good of this?' After

a combat situation, there are those that you become friends with,

and those you don't, and he was one that you did. We became

good friends, and you felt like you could talk with him. But to

my platoon sergeants or platoon leaders, you could never ask anything

like that because they were all 'Go Army', while the

rest of us, the Joes as they call us, are sitting around saying,

'Why are we putting our lives in danger for this?'"

Key continued, "I always felt bad that I wasn't there

during the incident when my sergeant lost his leg. I had just

finished an eight-hour guard shift, and they were on patrol and

then they got shot up with an RPG-17 that tore the legs off of

three people in their APC [Armored Personnel Carrier]. And they

later discovered it was actually one of the United States'

own weapons that was given to them during the Iran/Iraq war."

"It's coming across the radio," Key continued,

"so we're all waiting for them to get back and help

them as much as we can, and then they get there and you actually

have to sit there and pick up one of your friend's legs and

set it beside them so it's with them when they get medivaced

out. Our superiors then made us take their weapons and their vehicle

that was totally blood-soaked and told us that we had to clean

it all up. I'm like,'You've got to be shitting

me.' This was my friend, and that's all their blood,

and they're telling you that you have to clean it all up

so that someone else can use it."

After returning from Iraq, Key became aware that the administration

and the media were portraying the war to the American public as

a struggle against foreign terrorists seeking to disrupt "democracy."

"When I was in hiding I would watch the news trying to

see what exactly was going on, I just wanted to keep on top of

it," Key recalled. "And every day, that's all you

would have. You know, 'Two American soldiers die from terrorists,'

or 'Ten wounded from terrorists.' It was always terrorists - they

never consider it just being people that are fighting for their

country. It's still a war to them and they are fighting against

the invasion of their country.

"The American government just calls them all terrorists

and that's how they present it to the American public. Of

course the American public is very much against the idea of terrorists

ever since 9/11, so the government just focuses on that word,

and that keeps the war going. They think that if they say that

every American soldier that dies, that for all the boys and girls

that are being killed, that they are being killed by terrorists,

they can keep the American people behind it."

Key continued, "Even when I was there you're hearing

all the time about insurgents coming in from Syria, 'they're

coming in from Jordan, they're coming in from everywhere,'

and there may be a few, but for the most part they are the farmers,

they're the people whose homes you invaded for no reason

and took their family members off to jail and destroyed their

lives, maybe killed their son or their father and they want you

out of their country. They look at us as being guilty of war crimes

and we are. We impose killing, we detain them, we torture them - we're

the ones that caused it all."

As for the myth of Iraq's connection to Al Qaeda, Key

explained that he and other soldiers never bought into it.

Key recalled, "We were getting letters from back home

saying that everyone is being told that Iraq was linked to Al

Qaeda and we were all saying, 'There's no way that's

true.' Saddam Hussein didn't like terrorists, I mean

he was not a good man himself, but he didn't allow terrorists

into his country. We knew that he was not a radical fundamentalist

like Osama bin Laden - I mean there was no connection. But

we had all pretty much figured that out right away and we couldn't

believe that the American people were standing behind us because

they believed that we were fighting terrorists that were involved

in September 11, and that was basically Bush's reason for

invading Iraq."

In early 2003, back at Fort Carson in the weeks before leaving

for Iraq, Key was told that he would be there no more six months.

On the day before he left, the Army changed that to 18-24 months.

That was the same time that the military implemented a Stop-Loss

program, preventing soldiers who have served their full term in

the military from retiring or leaving. In Iraq, as Key recalled,

there was no sense of how long or how many tours they would have

to serve there.

When he was given two weeks leave from Iraq in November 2003,

Joshua and his wife and children climbed into a used car, left

the base at Fort Carson and drove east. They decided to stay in

Philadelphia, thinking that it was a big enough city to remain

anonymous. Running out of cash, Key took a welding job, and his

wife Brandi worked in a restaurant. For over a year, they moved

every 30 days to a new motel so people wouldn't ask questions,

all the while fearing a knock on the door from law enforcement.

Key was a wanted man, and the FBI had already contacted his

mother in Oklahoma, who hadn't seen her son since before

his deployment in 2003. Agents threatened her with being charged

with aiding and abetting a criminal.

One day, Key logged onto the Internet and typed 'Deserter-Need

Help.' He eventually made contact with the War Resisters

League in Toronto and lawyer Jeffry House, who advised the couple

to wait for their soon-expected fourth child to be born before

heading north.

The Canadian government of Prime Minister Paul Martin rejected

US soldier Jeremy Hinzman's appeal for refugee status last

March. The decision in this test case demonstrated Ottawa's

subservience to the Bush administration and the war in Iraq, while

leaving soldiers like Joshua Key, who have turned against the

Iraq war, to face an uncertain future.

|